Forty Years of

Wood Crafts by

Ryuji Mitani

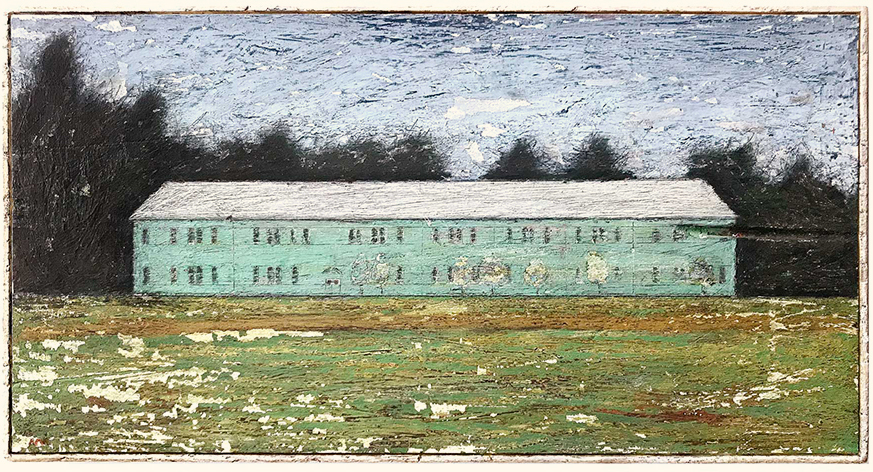

School Building

1988, 210 x 390 mm, Tempera Oil Pastel Board

Foreword by Nalata Nalata

Stepping into Ryuji Mitani’s studio and home in Matsumoto for the first time was a profound experience for us. After observing an urushi demonstration, we had a chat over tea served in hakuboku cups carved and lacquered by the artisan by hand. There are extensive books and articles where one can study Mitani’s philosophy on the Seikatsu Kogei (lifestyle crafts) movement, but it was clear in that moment that there was only one way to experience it: to best understand Ryuji Mitani, one simply needs to use one of his pieces.

Doing so reminds us of the role that these objects play in shaping our movements and interactions through the day, as well as the role we all play in bringing them to life. Whether it’s sharing a meal with a friend on usuzumi plates or eating rice from a noir lacquered bowl, each piece has a part in enhancing our moods and making us aware of the world that — much like Mitani’s craft — is ultimately shaped by human hands.

Mitani’s approach to craft exemplifies his way of living as it is motivated by boundless curiosity and a thirst for improving daily life. By drawing on the world around him — through theatre, literature, history, nature and his own personal interactions — he creates each piece to fill a void, to improve on a function, and above all to tell a story of how the object fits in the rhythm of a person’s life. As we celebrate the span of Mitani’s career, we hope that people all over will not only love the works as much as we do but also practice a way of life that celebrates the ordinary of every day.

Preface by Ryuji Mitani

1978

In front of a bank near the East exit of Shinjuku station, I laid a cloth on the sidewalk and sold folk-art wooden masks. I named my business Persona Studio.

Before I sold masks, I belonged to an avant-garde theater company in Kyoto.

“Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more.”

This is a passage from Shakespeare’s Macbeth, which my theatre company presented. I gave up and quit after six years.

Life on stage was ethereal, so dropping out of theater meant returning to the real world.

I had to reset my life with having almost nothing.

Since I had to start from scratch anyway, I decided to be a merchant as it was the most basic form of economic activity.

Six months later, I moved to Matsumoto, Nagano.

1981

I had a thought that perhaps I could try making a living with wood crafts. Although I had no money for a studio, I thought about what I could make in my small apartment at a public housing complex.

There my wooden brooches were born, as they could be made in a small, six-tatami sized room.

As odd as Persona Studio may sound, I decided to keep the name from my street vendor days for my new woodworking practice.

Brooches

It was February when I first carved Japanese linden wood to make my wooden brooches.

Kingfisher, grey wagtail, three subspecies of robins, cow, and horse — my brooches reflected things that I would encounter in the mountains and highlands near my apartment.

With five newly made brooches in my palms, I headed to small inns and bed-and-breakfasts in nearby tourist sites.

“These are just samples. I’ll make them and deliver them to you by April.”

In spite of walking in without an appointment, with much luck I got several orders.

I continued making and selling brooches to clients, and gradually, it became my career for ten years to deliver them to tourist spots like Hakuba, Tateshina, and Kamikochi in Nagano.

The “Children’s Scene” series in this photo were my homage to the little tin toys from former East Germany. I thought they would be a fun sight if I came across such little toys on my travels, so I made them based on this idea.

Cutlery

What can I produce in my small, six-tatami room?

The beginning of my practice was limited by space and resources, but I thought I’d just make do with what I have anyways.

Then I came up with the idea of making wooden spoons, which were the first practical things I made.

Spoons may be small, but their significance became immeasurable for my later life.

Wooden spoons are a good entry point to using wooden tableware, offering us a chance to feel the texture of wood in our hands and on our lips when we eat. It might be difficult for people to understand my wooden tableware without any wooden utensils.

With just a scoop attached to a handle, spoons have a very simple form.

Spoons are efficient and faithful to the function required of them.

Spoons may be small, but they fulfill the responsibilities that other utensils can't do. They may not stand out on the table, but they carry such a presence that feels complete and just right in itself.

Butter Box

When I was in high school, I came across the book Women! by Juzo Itami on my brother’s bookshelf. In the book, the author — who lived in Europe and learned the Western way of life — tried to find faults in the Japanese lifestyle and called for improvements.

In the book, Juzo writes, “First of all, I’d like to say that spaghetti is not udon.” “Let’s spend more money on tableware. At least, don’t put chopsticks in glasses or used bottles of mayonnaise.”

Many people who were shocked and inspired by Juzo’s book have written about its impact. We were fascinated with his distinct, colloquial writing style, his unique perspective on the details of everyday life, and his assertiveness. In the passage "Things in Every Morning” in his book, he said,

“Why haven’t we designed a container that won’t make a mess of butter?”

I immediately looked into the fridge while holding the book and found a butter case that was cloudy with oil and looking pitiful.

Juzo continued, “How about thick, yellow pottery for a butter case?” I was struck by how pertinent his observation was that it left a scar on me.

It was a long time later, after I started woodworking, that the butter box suddenly came to mind. It was then that I finally resolved the butter box challenge.

Craft Fair

The Matsumoto Craft Fair began with a group of young, independent artisans who came together when we had no place else to sell our work.

When my fellow artisans and I set up the blue tents for the inaugural Craft Fair on the lawn by the old wooden school, we all felt that something special was taking place and shared a sense of excitement around it.

Since then, the annual Craft Fair became a harvest festival of sorts for craftsmen. The two days of the Craft Fair was the chance to air out and share our ideas with customers far and wide under the glow of the sun.

I was in charge of making posters and flyers at the Craft Fair.

The poster in the photo was for the third iteration of the Fair, and the object in the poster was a miniature of the old schoolhouse that I made of wood.

Looking at the poster again, I smile wryly at the fact that the slogan “For a Life-Craft Balance” is still relevant now. Nothing has really changed.

Music Box

I made the music box in the photo when my two daughters were around 3 years and 5 years old.

I used to go to the city to buy gifts for my daughters, but that often ended in failure. After several unsuccessful attempts, I started to make toys for my daughters like wooden animal figures, a spinning top, a music box, a child’s chair, a rocking horse, and a bowl and spoon for baby food.

The mechanism I installed in the music box is from Switzerland and makes sounds by turning the handle either right or left. It is well designed so that toddlers who are not good at turning handles can also enjoy music.

Toys remind me of the film Circus by the American sculptor Alexander Calder.

In the film, Calder shows off miniature circus figures and animals from a large suitcase. Like a puppeteer of Joruri (traditional Japanese puppet show), Calder demonstrates horse acrobatics, tightrope walking, and lion taming with his toys in his grim wild-like face.

The film conveys how free his spirit was, traversing easily between making big, modern sculptures and children’s toys. It seems that for Calder, there was no distinction between the two.

Wild Cherry Wood Bowl

I started to make tableware with Ohyamazakura wood from the wild mountain cherry tree in Hokkaido. The dense, solid cherry wood is tough enough to be processed or sliced thin. The reddish hue that develops with age is perfect for tableware. That’s why I’ve used cherry wood for so long.

Outside my urushi studio, I planted a wild cherry tree. The tree was positioned in the garden slightly away from the studio since the tree will grow large. I look forward to the full growth of the tree with its branches spread wide and covered with leaves.

Woodworking generally means making furniture, but I sought to create small-scale home goods to bring wood closer into our daily life. My wooden tableware was born from this point of view.

Wooden tableware can be useful for daily meals. By using wooden tableware, we become more familiar with the material. The more we touch wood, the more we like wood. So that when we go to the mountains, we might feel a more intimate connection to the landscape.

Wood has been used for the objects closely tied to the human body, like the arm of a chair, a table, and a handrail. The warmth and gentle texture of wood is distinctive and special, unlike any other material.

I am so lucky to spend so much time touching wood every day. It is truly a blessing.

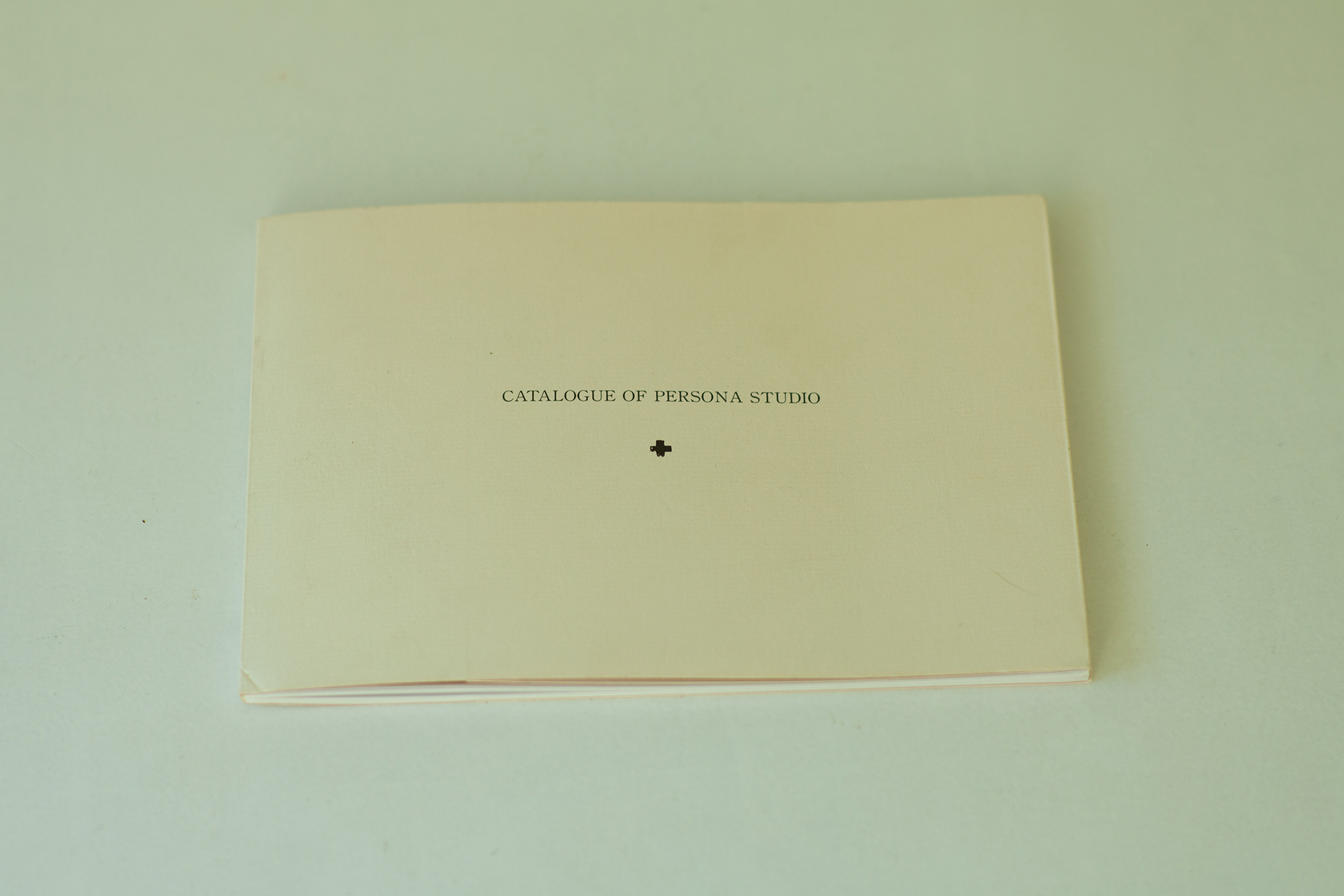

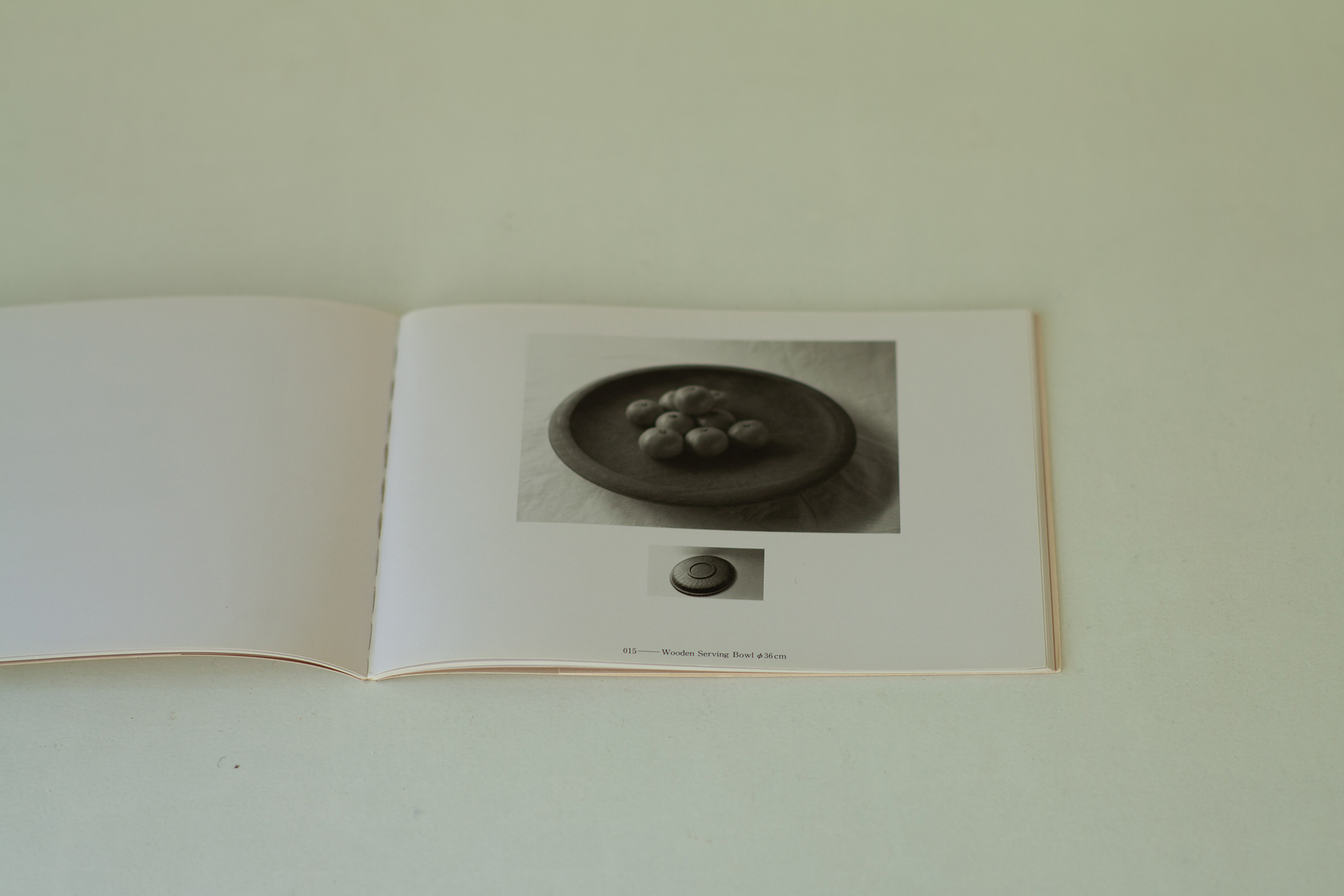

10th Anniversary Catalogue

After ten years of selling brooches around tourist sites, I decided to dedicate myself to making tableware.

I visited shops that carried my brooches to express my gratitude.

“I’m going to change the direction of my work,” I told the shop owners who supported me when I couldn’t make a living. “Good luck!” I am grateful for their encouragement.

Yet, some of them didn’t look happy for me. I might have disappointed them and broke some part of our relationship, for which I felt very sorry. I knew there would be difficulties ahead in changing directions to pursue woodworking that felt more gratifying.

The end of something is also the beginning of something.

I put my complex feelings from each moment of those last ten years into making the 10th anniversary catalogue seen in the photo. The monochrome photo was taken by me. The printing process was handled by my brother.

Jindainire Square Plate

Jindainire is wood derived from the parts of trees that have been buried for a long time, often downed by typhoons or floods and then covered underground for over 1000 years.

I visited a lumber storage yard where only buried wood is stocked. The wood was more like a fossil than it was wood. It took on a black color and crumbled with the slightest touch. I thought the wood might return to soil. Jindainire changes by the power of nature underground, lending it a distinctive appearance and subtle nuance in color.

When I changed direction and specialized in tableware, I took it as a great opportunity to accomplish another task I had considered for a long time. Painting — that was what I wanted to do.

I had never learned to paint nor had I hoped to be a painter. I just liked the idea of painting for a long time. When I turned 40 years old, I thought the time had come. I would need to be full of energy if I want to paint for the rest of my life, so the timing was just right.

First I gathered and patched wooden boards and then painted them in white. I made tempera paint from scratch by mixing fresh egg yolks, resin, and pigments. It doesn’t have to be great. I just wanted to paint what I like and that would be fine.

Painting should be for oneself.

Black Urushi

The natural hue that oil finish expresses on a wooden vessel is my favorite, but the film on the oil coating easily fades from the surface when hot soup is served in it.

I thought urushi was the best solution to solve this problem.

After I purchased urushi for the first time, I opened the paper lid on the package and found that the caramel color of urushi was brighter than I expected.

Once urushi was exposed to air though, the color instantly turned dark brown.

I was a bit disappointed and thought that the brighter color of urushi would be more ideal to make the wood grain of the vessel stand out. I knew it was impossible though.

When I started urushi work, I decided to go with a black color.

Black urushi vessels can make green vegetables look nice, and it can also be used for both Japanese and Western cuisines.

That was one of the reasons why I wanted to make black urushi vessels.

The chiseled lines emerge so distinctly when applying black urushi on wooden vessels. Its appearance seems almost sculptural.

A large wooden plate is not heavy like pottery. That should be a requirement to be enjoyed daily.

Plum Blossom Dish

A snow scene is the most familiar landscape for me.

Snow through the windows, shimmering snow blanketing the roads, icy snowflakes falling on my face when I look up at the black sky. When I was a kid in my hometown Fukui, we had heavy snowfall every year that covered the first floor of the house completely.

White wall, white paper, white canvas, white shirts... when someone asks me about my most favorite color, I always answer white.

A long time ago, people all over the world were fascinated with the brilliance of Hakuji white porcelain. Attempts were then made to make white pottery using clay that resulted in different types of white vessels, like Kohiki (white slip ware), Shino ware, and Delft ware.

Like many people, I longed for white tableware.

Eventually I made this plum blossom dish and applied white urushi for the first time.

In regions where winter is long, plum blossom is an eagerly awaited sign of spring.

I made the plum blossom dish to bring such joy and anticipation for the warmer season, as if to adorn the room with a single flower.

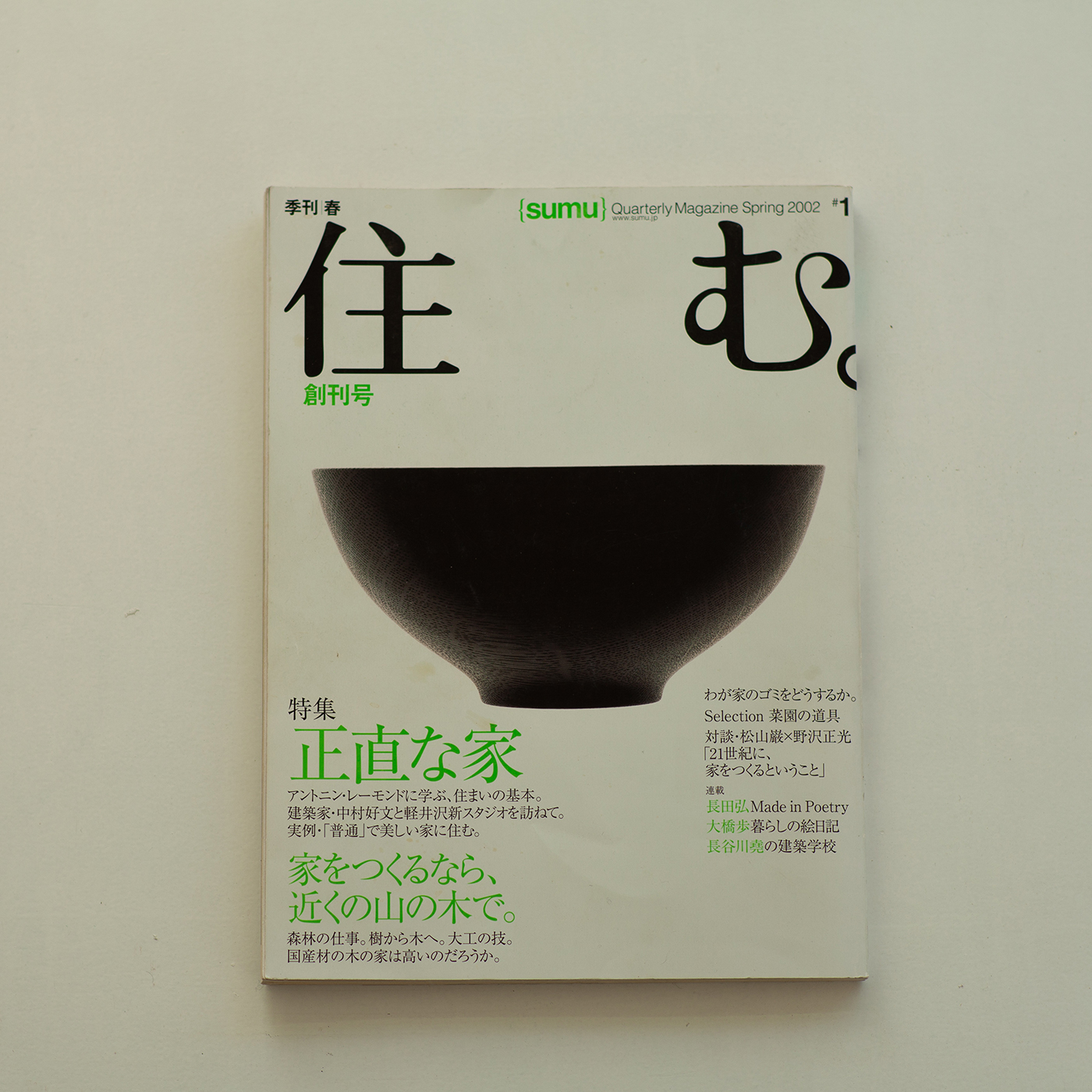

Magazine called ‘Sumu’

I started a regular column “Take a Stroll in my Everyday Life” for a new lifestyle magazine Sumu, which means to inhabit in Japanese.

My main topics weren’t just about the living world and the landscape seen from the window of my house, but also things overlooked in the distance.

Right after the first issue of Sumu magazine was published, I held an exhibition. Surprisingly the customers at my exhibition were a lot younger than usual, I would say by about 20 years. I thought, what a huge impact the magazine made, but actually it wasn’t the case.

This was around the time of great social and economic upheaval in Japan, with the burst of the bubble economy causing bankruptcy in the banks and security firms. This new era was called ‘Shushoku Hyogaki,’ which signaled the “Employment Ice Age” for new graduates and job hunters, as well as increased gig employment and ‘hikikomori’, a form of severe social withdrawal that became a big problem.

It is true that Earth’s resources are limited. A lot of people started to think, “We have to alter our mass consumerist lifestyle,” “we have to control our desires and step on the brakes,” or “we have to make the world more sustainable.”

With the rise of the Internet, economic globalization accelerated to mixed effects. On the one hand, open borders made it easier for everyone to connect, but on the other, it also became easier for communities to become divided and isolated from one another. It was the beginning of a rough time. Despite such difficult conditions, there were still a myriad of people who lived their own lives looking towards their future.

Poverty is not simply a lack of money. It is also the state of relying blindly on a value system imposed by society and the inability to find significance and value for oneself.

Those who can live without the overabundance of material goods and information are the ones who carve their own path for their future.

White Urushi Rounded Square Plate

A tree, once rooted, stands forever at the same spot. A tree grows leaves in spring, never forgets to absorb the water in summer, endures strong winds in autumn, and hibernates in winter. Animals may wonder if a tree gets bored, but the tree would answer, “We’re busy all year round doing one thing or another.”

Animals with strong desires are easily bored when they have the same routine every day. If we didn’t get bored and get jealous, we would be more than happy and peaceful everyday. Being an animal is nothing like being a plant.

Our lives are based on routines repeating every day, so it is important that we find a way to live happily without getting bored. As one solution to this, humans might have invented cooking and creating tableware to enjoy every meal as much as possible.

That’s why in my home, fukinotou tempura (battered then deep-fried butterbur sprout) or deep-fried spring rolls are served on this white urushi, rounded square plate.

VAT

Looking back at 37 years of Matsumoto Craft Fair, it seems like the years between 2005 and 2009 were the most impressive. A mass of up-and-coming artisans emerged one after another in that period. Most of them were born in the 1970s, reaching their 20’s in the midst of the “Shushoku Hyogaki” era. Perhaps because of this difficult time, some have decided to become artisans and work with their hands for a living. Anyways, the time around from 2005 to 2009 was delightful.

I also started making these deep square trays in 2008. I named them Vat because they looked like film print developing trays in the darkroom (the trays are called vat in Japanese).

Pottery is usually made on a wheel so that the shape inevitably becomes round, but in woodworking, we cut the long lumber first to make tableware. It means a square shape is more appropriate than a round shape. If we try to make round tableware from the lumber, we need to discard the triangles at four corners.

Square shaped vessels are useful. They are easy to stack, and they are suitable for square shaped food like sandwiches. When square shaped vessels are laid out on the dining table, they make a unique appearance in combination with round vessels as well as a beautiful display without bothering the other vessels.

10cm

A tiny house built in the Taisho era (around 100 years ago) had been standing on the Rokku shopping avenue in Matsumoto. One day, I was surprised to hear that the owner is going to tear down the house. “That’s going to be a big loss. Please rent it out to me,” I asked the owner spontaneously.

That was the beginning of 10cm Shop.

I have often been asked over the phone by travelers to Matsumoto if there’s a place where they can see my works. I had considered it for a long time, and I think this helped pull the trigger to open my shop.

When I was younger, my favorite book, clothing, and general stores were an entrance into the world of adults. I thought that if I were to open a store, I would want it to be like one of those places.

The presence and influence of small businesses are particularly huge in the countryside because our fascination with the city depends on whether there’s great shops or not.

My ideal would be to bring together various people in the neighborhood and slowly cultivate communal places where our spirits can gather. It might be harder now to create communities where people in Nagaya—a popular housing complex under the same ridge during the Edo era—care for one another as they are depicted in stories by rakugo artists, but I think it’s still possible to take time to build up a place that is shared and enjoyed by everyone.

White Urushi Shinogi Pitcher

In 2012, I participated in an event* under the name of 12cm Shop. 12cm is often used as the size of Japanese rice bowls and soup bowls.

Such measurements, which are determined by human bodies and actions, are fun to know. The diameter of the pitcher in the left photo is 7.5cm, which is the same diameter as the large bottle of beer. It is said that 7.5cm is easy to grab with one hand.

In the same year, I participated in the inaugural Seikatsu Kogei Festival in Setouchi, a region along the Seto inland sea.

Another craft festival called Rokku Craft Street was also held on the street in front of 10cm Shop.

So many events have happened in the world in the 28 years that I was a part of the Matsumoto Craft Fair.

Finally, I thought it was time to do something different.

For the Seikatsu Kogei festival, I often visited Takamatsu. After arriving at Takamatsu station, I got on a small ferry to Megijima island at a port near the station. The sea breeze felt nice. I loved the quiet but sparkling surface of the Setouchi sea.

It has been a while since I last visited. I really want to see the sea again.

*Ginza Mekiki Hyakkagai at Matsuya Ginza

Hakuboku Deep Bowl

For its 32nd issue, the magazine Hibi published “Resume of vessels by Ryuji Mitani”.

The editor-in-chief of Hibi, Yoshie Takahashi-san, was a great cook and made many dishes for this book.

“A deep bowl is great since it makes food served in it look beautiful, even when there is little food left in it,” Takahashi-san told me while she was serving food in this Hakuboku deep bowl.

The way Takahashi-san edits is like taking a trip without a destination — she doesn’t decide in advance where a story will go. When we covered a story for the magazine together, she tried not to make appointments to interview subjects in advance.

Even when her colleagues and her interviewees worried that they had no idea where an assignment was going, Takahashi-san seemed quite unconcerned. Her relaxed and flexible attitude can be read in the soft and subtle tone running throughout the magazine.

Her magazine Hibi was always finished as if pieces of everyday life were gathered in a book or as if bright sunlight from the window was trapped and bound directly.

White Urushi Zelkova Platter

I have handled many types of wood out of curiosity, but zelkova was the only exception. I had tried not to use it, as it was honestly not my favorite at all.

For example, the powerful grain in Funa-dansu (shipboard chest) made with zelkova is emphasized by urushi finishing. And because of its iron hardware, which looks like armor fixed firmly to wood, the appearance of Funa-dansu seems just as aggressive as a Samurai of the Sengoku period. I would say that’s too much.

As another example, Agarikamachi—the thick wood board at the front edge of the entranceways on Japanese houses—is also made with zelkova. Its presence dominates the entrance as if it owned the place and ruins the harmony of the interior.

Zelkova always seemed selfish, self-centered, and ostentatious in its luxury.

One day, I asked Kijiya (Japanese woodworkers particularly engaged in wood turning) to make a few small plates using their zelkova wood. Once I applied urushi over the small zelkova plates, its rough grains repelled the glaze to express a distinctive and beautiful character (the natural effect is called Mehajiki).

I admit, I might have had a prejudice against zelkova. When zelkova is used for small woodcraft by the right person in the right context, it can be pretty decent. After all, it depends on how it is to be used.

Now I feel like I want to apologize to zelkova.

White Urushi Bowl

In 2015, six artisans including myself had a group exhibition called Tatazumai in Paris.

Mingei is well known overseas, but Japanese crafts beyond that seem hardly known at all. I think the reason Mingei is widespread is thanks to the British potter Bernard Leach who enlightened his audience about it, as well as Soetsu Yanagi and Shōji Hamada who often visited Western countries.

I thought I should start a similar effort to convey and enlighten the world about broader Japanese Crafts little by little.

My very first exhibition overseas was at Xio Man in Taipei in 2012. When I was there, I felt like local people had great interest in Japanese crafts. I heard that there are many artisans designated as Living National Treasure in Taipei, but it’s rare to find young artisans who create and sell daily tableware for a living like the young artisans in Japan. I assume that craft is very special and outside of daily life in Taipei, whereas in Japan it is still common for people to use tableware every day. Thanks to a large number of tableware lovers and craft enthusiasts, Japanese artisans can keep making work.

Makers, connectors, and users—these three people are necessary for the continuance of Japanese craft culture.

It has been 10 years since my first overseas exhibition. I feel a passionate gaze growing more and more for Japanese craft. Seikatsu Kogei will probably become more popular around East Asia in the future, which I hope will inspire people to experience more joy and comfort in their everyday life.

Coffee Tools

My morning ritual is to brew pour-over coffee.

I fill the kettle halfway with fresh water and then put it to boil. A canister in my kitchen is always filled with my favorite coffee beans.

The accurate ratio of coffee beans to water is 4 scoops to 400cc of water for two. After grinding beans with a coffee mill, I then put the ground coffee into a paper filter over a dripper.

The first step is letting the ground coffee bloom with a little hot water.

The liquid then slowly drips a rich, chocolate color while I pour the remaining amount of hot water. This process seems most important. Curiously, every day I do the same steps, but the taste of coffee always varies.

I use the white urushi soba choko as my coffee cup.

I would say, the more I am fascinated with something, the more I am curious about the tools around it. Gradually my collection of tools for making coffee grows.

A Bird of Imagination

“Urbanization transforms rural land into towns and then cities, but city living completely erases our memory of its origins. City life is centered around humans and their thoughts, making them believe that everything proceeds according to their rationality.

And yet, the natural world has its limits, with phenomena like extreme weather and the pandemic keeping our arrogance in check. They remind us of how small and insignificant humans are.

We believe that economic development and aiming for greater heights will lead to our happiness. We strive so hard to reach these aims, but how much higher do we go before we can finally be happy?

No bird / can fly higher / than their imagination” *

I realized that the world where people live is not so big — their house, their neighborhood, the stores they regularly visit, and the people they frequently see. Our essential needs are a small house and the household goods and tableware that fit into the house. That should be sufficient.

The aim of Japanese crafts is to enrich our lives by improving the inconspicuous objects in our daily life. Instead of indulging our desires to aim increasingly higher and chase illusions and fantasy, by enjoying a cup of tea in our hands, we can learn to seek satisfaction for mind and spirit.

An imaginary bird can fly in the big sky from even a fragment of everyday life.

*Terayama, Shuji. “Hands Full of Words”, Shincho Bunko.

Wooden Boat

The number of Chinese tea enthusiasts has been increasing.

The way to serve Chinese tea is beautiful and comforting. Since there’s a lot of flexibility with the tools used for Chinese tea compared to Japanese tea ceremony, artisans like me take great pleasure in thinking about new ideas for it.

Both the tense atmosphere at a Chinese tea ceremony and the more relaxed vibe while drinking Chinese tea with close friends are delightful. The distance between people grows closer when we drink Chinese tea.

The item on the ‘Kissa bon’ (tea tray) in the photo is a 'Chasoku' (tea scoop) made in the shape of a boat.

The sea surrounding East Asia opened a long time ago, and trade and travel over the sea flourished. A long time ago, Chinese philosophy and habits were gradually adopted into our culture over centuries. I feel they are now rooted deeply in our daily life.

We are companions who share the same sea of memories. I made this small wooden boat to cross the sea of memories. Let’s ride on the boat to see friends and sit together over delicious tea to talk leisurely — that is my wish.

Crafts of Weakness

The Japanese have cherished both the weak and the poor simultaneously.

It means that we admire beauty in the way of Wabi-sabi or in things just found at our feet, rather than valuing perfection or its justification.

We adore a cup of tea in a humble tea room rather than at a fancy dinner in a luxurious banquet. We appreciate someone who lives frugally and supports disadvantaged people, instead of a person who is a great leader with power.

Many people were uncomfortable with the vanity, greed and extravagance associated with the bubble economy before it burst. To regain our lost sense of self from the illusions we indulged about the economy, we spent more time with families and focused on living within our means. Seikatsu Kogei was born to meet such demands and needs.

Most things created as Seikatsu Kogei, like daily tableware, are simple, plain, and quiet—without golden glow or excessive decoration to feast our eyes upon.

However, such things might have been necessary for us to recover a lifestyle that was lost in the modernization of Japan. The rooms in a house really only breathe and become lively when people live in it. Similarly, our hollowed-out life might just need crafts of the weak and poor to be fulfilled yet again.

Author: Ryuji Mitani

Photos and Cover Art: Ryuji Mitani

Translator: Aya Nihei

Copy Editor: Vicky Wong

Graphic Design: Studio Newwork

Programmer: Nao Fujimoto

Online Publisher: Nalata Nalata

First edition book published by 10cm in Japanese, March 2021