うつわのそれから

三谷龍二

crafts,

and then

–

Ryuji Mitani

To connect to something.

To connect with someone.

Hello there.

Can you hear me?

1

For quite some time, handcrafting has existed as a form of self-expression. Utsuwa, however, was never an art form that could exist on its own, as a vessel cannot fulfill its role without both someone to cook and another to eat. Its final form emerges through connection, not just a one-way interaction.I’ve taken this text as an opportunity to reflect on and reconsider these vessels that exist intimately and in proximity to our everyday lives.

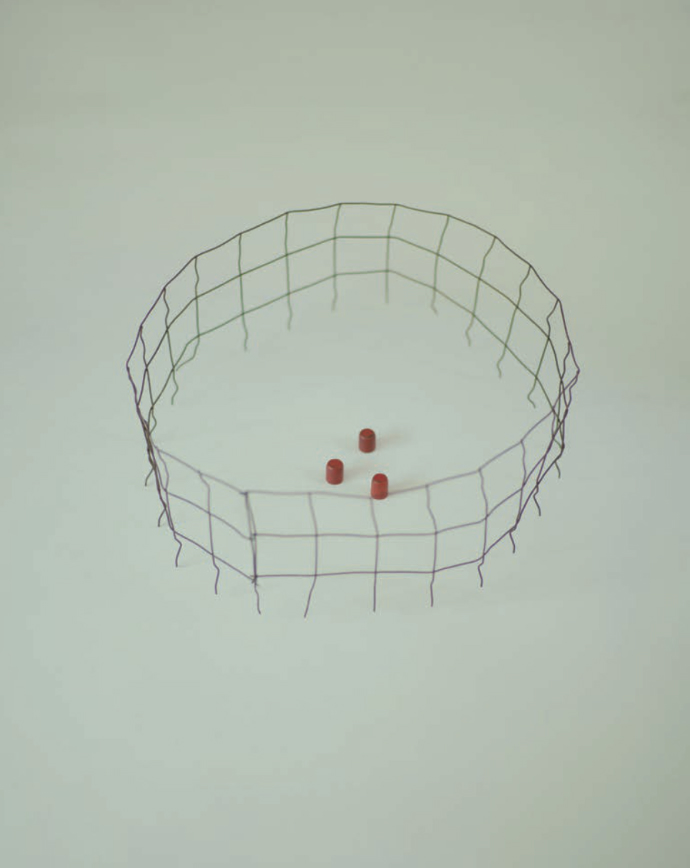

2

Individuality and freedom seem to have lost their brilliance in recent years.I suspect that it’s because people sought individuality and freedom in excess and at the cost of shared values, ultimately pulling apart the familial and community connections that had gently embraced us together. Today, we live trapped in an invisible cage – complacent with a vague sense of stagnancy while relinquishing ourselves to a tentative sense of freedom.

Even then, so as not to avoid giving up on living, we reach out for tools nearby and swing a hoe towards the vast land we know to be ourselves.

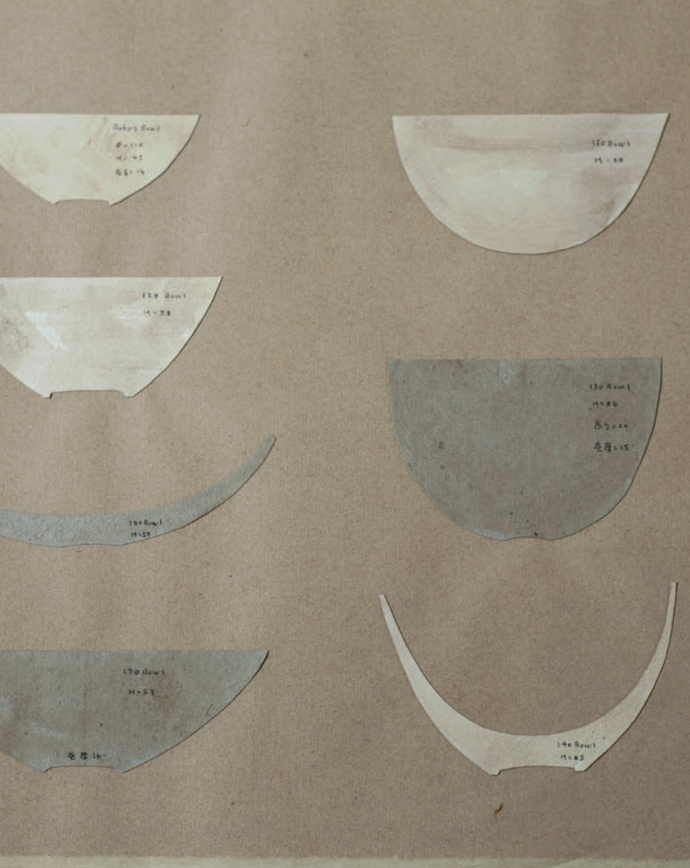

3

The ideal ratio for tableware is probably somewhere along the lines of half vessel and half food. Instead of filling it with just your own thoughts, you leave half for someone else. The existence of white space allows others to add new thoughts, so you must hold yourself back and avoid creating too much.

Through this practice, I teach myself to exist outside of my own self. Utsuwa (which can also be represented with the character empty) is about emptying yourself. The half emptiness of the vessels creates a lingering feeling that allows me to repeat this craft again and again. This is what makes these utsuwa so interesting.

4

Natural disasters and epidemics have prompted us to consider the importance of mundane everyday moments. When sucked into a greater, uncontrollable force that does not know to stop, we are forced to enter a state of high alert that makes us experience all dangers of life with our full senses, just like flocks of birds that fly into the sky at once before an earthquake hits. In my craft, you connect to nature by touching clay, wood, and grass. By listening to, and then surrendering to the voices of the materials, you untie the armor of your ego. They say that crafting is about knowing when to stop, and it’s because human interference strips materials of their life force.

Deliberately and slowly, our hands interact with the world in a different way than our rational brains.

5

The time we spend eating meals at the dining table helps to ease the hardships of our days. Even verbal conflicts are resolved when you gather around a table. Delicious flavors transcend reason: it brings altruism (your friends’ joys) and personal benefit (your own joys) together in an embrace. At the end of the day, life is just an amalgamation of subtle everyday moments, and yet humans have found a way to continue it for thousands of years. Blessed be these ordinary days and eternal living.

6

Once made, what kinds of human stories do utsuwa vessels encounter? At the end of the day, they are simply houseware. And because they don’t project a strong sense of self, they are able to form many relationships and access the true essence of people’s everyday lives. It is at times this basic purpose of utsuwa – to be a tool to help live life with more joy and emotions – that resonates the most strongly with me.

Let museums take care of sophisticated art. Let us instead seek beauty in our footsteps and things at our feet that we take for granted. Let us focus on real and grounded experiences like satisfying our thirst with the most delicious water that fills our bodies with energy.

7

Japan has long been revered for its ability to create crafts with careful consideration of its users and attention to detail. And yet, when I called about a repair the other day, I was met with an AI-generated response. I can only assume that we are collectively moving towards a world driven by productivity and efficiency that deems human labor a waste. But are we really saying that we have come to terms with the inherent coldness and crudeness that will emerge from such a world? Perhaps this user-centric approach and attention to detail is outdated and inefficient. But the subtle oscillations and noises we experience with our bodies exist at the core of craftsmanship and will be what we makers continue to pursue.

8

In this “Small Time” exhibition series I’ve been working on for the past few years, I think that I’ve been reflecting on “individual moments” that emerged due to losing touch with the greater story that we had shared before. By collecting any smaller fragments I could find, I must have been trying to patch my story together.

Crafting vessels saved me from being stuck in a state of loss. There is an inherent joy that emerges from knowing that I am always connected to someone through utsuwa.

9

Makers spend their days staring at their own hands. It means that we have a narrower perspective. On the other hand, however, techniques can only be mastered through repetition; so perhaps it’s a necessary practice. In my craft, there’s a practice known as Shu-Ha-Ri (to protect - to break - to leave), in which we learn from the past, remain skeptical of new trends, but also acknowledge that we must leave the status quo. Peeling ourselves away from the familiar comfort of our world and, like a bird, looking at the world from a higher perspective -- this is the perspective that users can provide makers.

10

There was a time when making things with your own two hands was the norm. Everything one needed was made with their own hands. The labor was never easy, but it also came with joy.

Nowadays, we use money to acquire what others make. Life has most definitely gotten easier, but it’s come at the cost of many of life’s joys. Isn’t the effort and hard work you put into creating something in and of itself the most tangible way to experience living and feel it more intimately? It helps us regain the bond we once had with things.

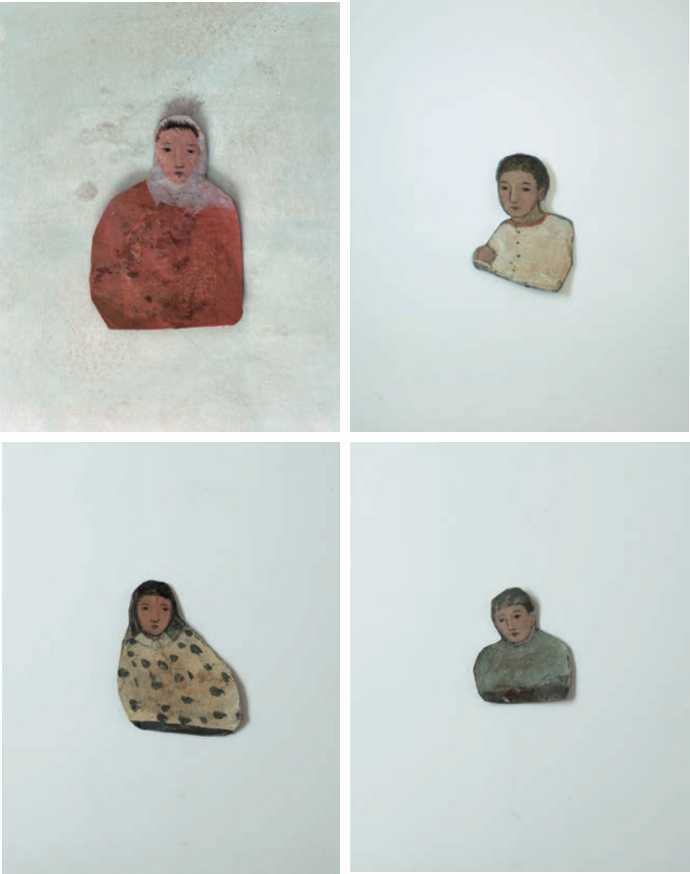

11

Small, fragile things often move me. It’s not those who are headed right towards their goal, but rather the subtle movements I see in those who are lost and standing still that fill me with a sense of endearment. Their wavering gaze. The slight expressions of their hands. My work embraces small details. And through something as small as utsuwa, I truly hope that I’m able to access something greater.

12

Whether it comes to art or films, every time I make a collection of things I like, I tend to prefer those that leave a stronger emotional impression on my heart. It makes me think that those that capture beautiful human emotions – rather than objective thoughts – tend to stay with me.

13

To live

To survive

Utsuwas are containers that hold the everyday and the spirit of people.

14

I have no doubt that in ten years and in some house, an utsuwa will hold a delicious meal and be surrounded by bountiful laughter.

Author: Ryuji Mitani

Photos and Cover Art: Ryuji Mitani

Translator: Aya Nihei

Copy Editor: Risako Yang

Graphic Design: Studio Newwork

Programmer: Nao Fujimoto

Online Publisher: Nalata Nalata

First edition book published by 10cm in Japanese, April 2023