The Man Behind the Woodworker

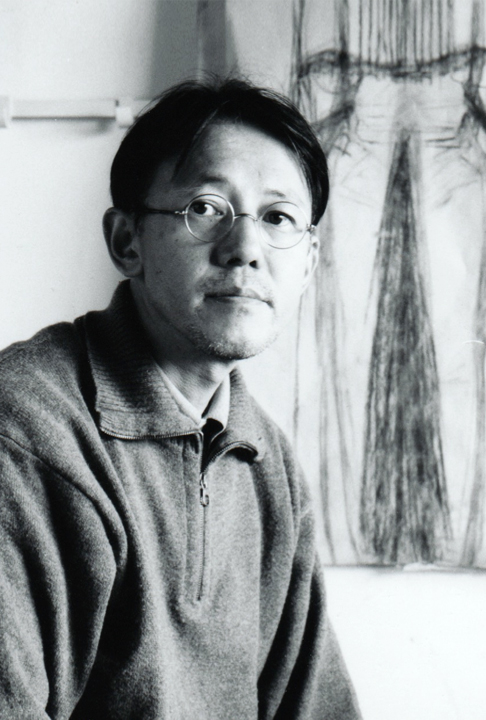

My conversations with master woodworker Ryuji Mitani across the years of our acquaintance have revealed him to me as a truly extraordinary person. His work holds both great beauty and skill, and I could write an entire thesis on its merit. However, I believe that getting to know Mitani-san, the man behind the woodworker, will be more interesting than pages of my interminable praise. I hope that after you read his story, you’ll enjoy his art with new perspective. Let’s start!

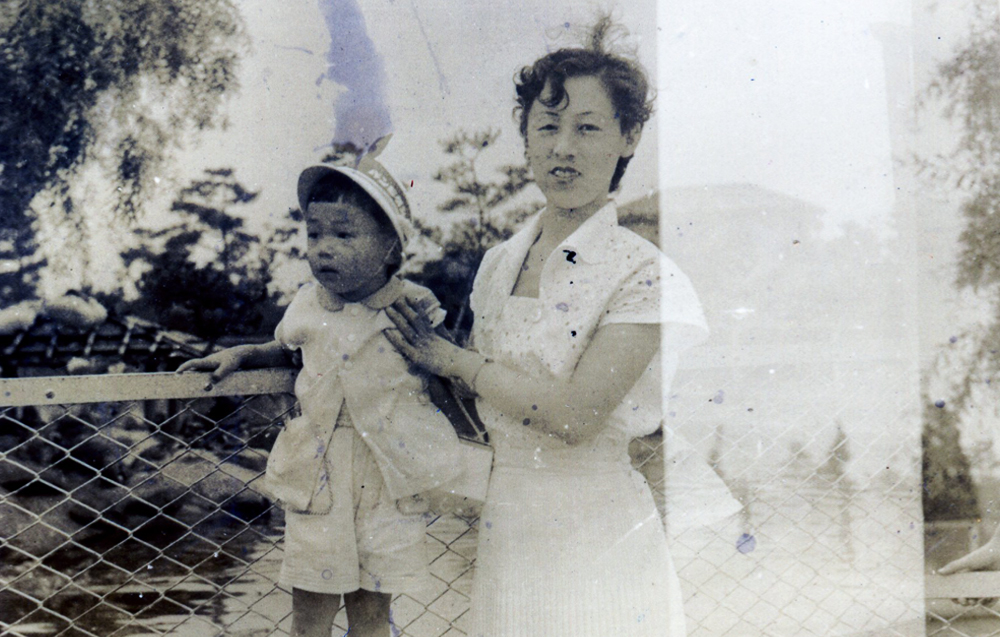

Mitani-san was born in Fukui city in Fukui prefecture the year of 1952. His life began to change at age 19 when he joined an avant-garde theater company in Kyoto. He joined not in hopes of becoming a great actor, but to help in designing the company’s show posters. “Eventually, I was asked to act in my first play – Salome by Oscar Wilde. But my pronunciation was unclear. I realized that I wasn’t really meant to be an actor [laughter].” Though he performed in several shows, he knew that it was not his path: “Being in the theater company was like being in an unrealistic world… I wanted to work on something real, to create something with my hands… Plus, I prefer to work alone.” After six years, he left the company.

Then, the young Mitani-san began to think about his next step. He thought of becoming a graphic designer as it came easily to him, but it was not his preference. He wasn’t sure what to do, but he had a general vision, explaining, “I just wanted to be independent and engaged in fundamental business.” He dreamed of becoming a fisherman, but when he told his friend he couldn’t swim, the friend advised: “Give up.” One day, he happened to stop into an art supply shop in Fukui and emerged with a woodcarving knife. As Mitani-san looks back on that little purchase, he says, “That was the very first step for me to becoming a woodworker.”

He started a day job in Chino working on road construction, and in his spare time, he would carve pieces of wood. During a visit to Matsumoto, he encountered something that would alter his path again – handmade wooden masks with whimsical, expressive faces based on the dōsojin, a deity said to guard over travelers. The masks were known as the folkcraft of Matsumoto, and Mitani-san was struck with an idea: “I will become a merchant and sell these masks!” Working alone selling merchandise was a basic kind of business. The idea to peddle masks became his answer.

He purchased them in bulk and headed to Tokyo. He began to sell the masks right away, with no plan, no connections, and no expectations. Against the odds, he made his way selling about three masks a day. “The sales each day totaled to around 5000 yen… acting in the theater company must have helped my acting skills as a salesman! [laughter]” And in his spare time, he continued to carve, sometimes making his own wooden masks using his merchandise as reference.

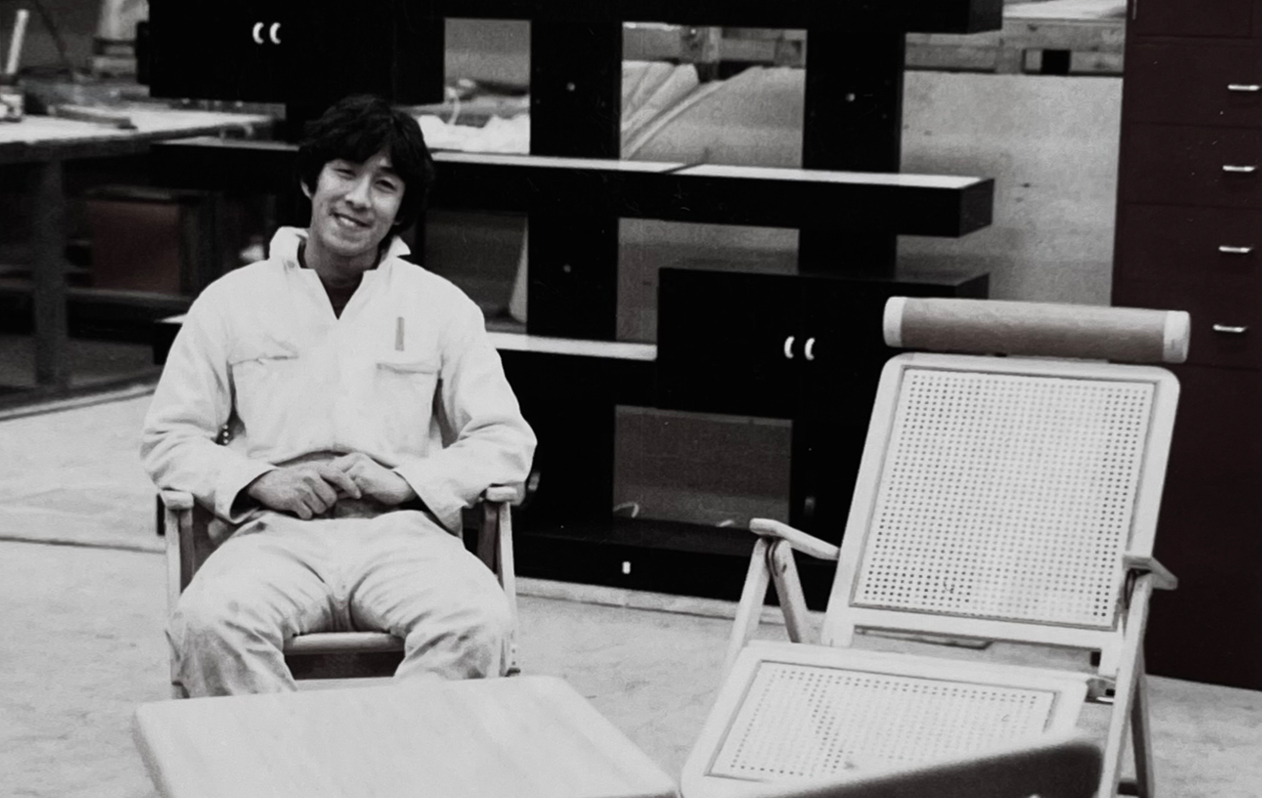

One day, the company from which Mitani-san bought the masks offered him a job in Matsumoto. He left Tokyo immediately and moved into a small, six-tatami room in a public housing complex after getting married. Matsumoto’s low humidity climate makes it suitable for dry wood and lumber, and the city is well known for its production of wooden furniture and crafts. For Mitani-san, it was a portal into the world of woodworking. He enrolled in a local trade school where he began to learn the art of making wooden chairs.

When his wife gave birth to their first child, Mitani-san faced reality: to support his family, he needed to make more money. He knew he wanted to make a living from his woodwork, but he didn’t have the means to buy large equipment or rent a workshop. He decided to make wooden brooches.

Mitani-san explained, “Woodworkers who’ve studied furniture-making in school don’t think about brooches. It hurts their great pride. But I didn’t have such great pride. That was good for me.” He began to carve and paint pieces of wood into brooches in the shape of animals, like a cow or a fox. They were small, fitting in the palm of your hand. He then sold the brooches in his neighborhood by driving between small inns and bed-and-breakfasts. The little brooches had a charm that stood out, and sales were good. “Plus, I must have seemed pretty desperate to the owners of the inns. That’s why my sales were so good [laughter].” He would continue to make and sell the brooches for another ten years.

Around the year 1984, Mitani-san began to make wooden tableware with the goal of having them be affordable for ordinary people. His butter cases, spoons, and bread plates for Western foods in simple, modern forms were designed for everyday use and differed from traditional Japanese tableware. He saw possibilities in less popular materials. He says of his philosophy, “A different perspective makes the unattractive attractive. We can find such possibilities everywhere around us.” For instance, cross-grained wood was the popular choice due to its convenience for mass production. But Mitani-san preferred straight-grained wood, explaining, “The grain pattern of cross-grained wood is noisy. Straight-grained wood looks calm and refined.” Urethane was commonly used as finish for its uniformity in large-scale industry, but Mitani-san preferred using a natural oil finish. It was safer for pieces like tableware, which people would touch to their mouths. And unlike a thick layer of urethane, oil finishing allows the beauty of the wood to shine.

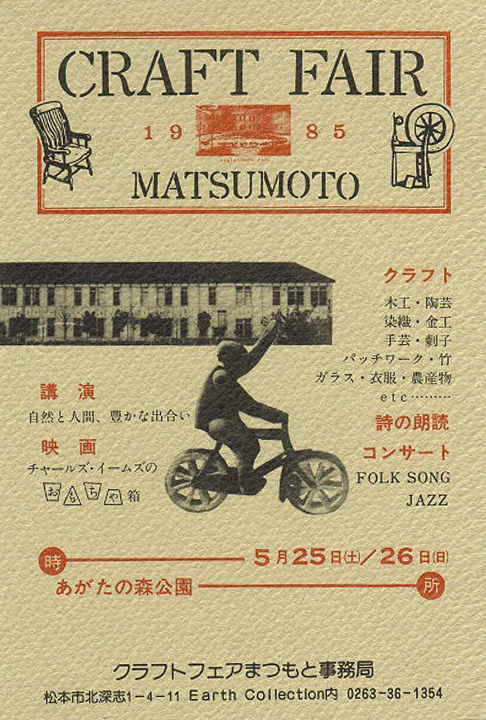

In 1985, at the height of Japan’s “bubble economy”, people were devoted to mass-consumption: “Mass production started as a way to enable a luxurious life for as many people as possible, right? But it resulted in the production of so many things that people quickly stopped consuming. From the resistance to that, Seikatsu Kogei came to be.” A lifestyle crafts movement seems incompatible with that era, but Mitani-san explains, “There were enough people who could sympathize with us. The disquiet probably began around the 1970s”. The 1970s marked the endpoint of the period of high economic growth that began in the 1950s. “People purchased the same items and wore the same things while the economy continued to grow. You could call it a kind of unity, that the Japanese people were convivial singing the same tune. But by the 1970s, we came apart and were lost again. People needed to seek their own way of living. It was the beginning of groping in the dark.” In response to the times, Mitani-san and his friends launched the very first Matsumoto Crafts Fair inspired by a quote from Tarkovsky’s film Nostalgia, “Society must become united again instead of so disjointed. Just look at nature and you’ll see that life is simple”. Soon the bubble economy burst in the beginning of the 1990s. People who had managed to sustain the dream of the bubble economy were then forced to pursue their own life once more. Mitani-san says, “After that, more and more people began to realize that there’s more to life than money.” And since that very first Crafts Fair, the culture of Japan indeed shifted to value a deeper enjoyment of life. Simultaneously, home goods shops that carry artisan crafts like the wooden tableware made by Mitani-san, started to emerge in Japan.

As Mitani-san evolved, so did his work. He began to experiment with “urushi” lacquer, a lacquer made from the sap of Toxicodendron Vernicifluum, commonly known as the Chinese Lacquer Tree. Used in Japan for thousands of years, the lacquer must be applied and cured layer by layer in a laborious, complex process that not only protects the wood but also highlights the beauty in its grain.

His first urushi items were made with black urushi as part of a series titled Noir. Traditionally, black urushi-ware in Japan had a high-gloss finish. Mitani-san thought this aesthetic was too fussy and unapproachable – not suitable for the everyday modern lifestyle. Inspired by the black colored CH24 Wishbone Chair by Hans Wegner, Mitani-san began to create a new kind of urushi-finished tableware. The strokes and grooves from his hand-tools were embraced rather than hidden, and the pieces had a subtle sheen that differed entirely from the mirror finish of classic urushi-ware.

But Mitani-san wanted to explore further. Though black and red urushi-ware were commonplace, white urushi-ware was almost nonexistent. He realized, “To truly modernize the craft, the color white was the answer. White urushi had never been used for tableware, only to paint faces and bodies in lacquer art.” Once again, Mitani-san saw the possibility beyond the rule. The basic process of his white urushi lacquering first requires the application of black urushi onto the wood followed by white urushi. Afterwards the piece is sanded with sandpaper and another coat of white urushi is applied. He explains his distinct process: “If I dab white urushi heavily on wood, it would look no different than plain white paint. I realized that lightly applying urushi stroke by stroke had a lovely painterly effect. The strokes of the brush were visible, but that made the surface more interesting.”

Mitani-san categorized his white urushi techniques into three distinct finishes. First, the basic white urushi: He applies several layers of white. The end product is white save for the bottom, where the black urushi remains uncovered. With Hakuboku, he lacquers the inside of the vessels in white and the outside in black. In the third technique of Usuzumi, he applies a nearly translucent layer of white urushi over black as a way of highlighting the darkness below, producing a finish as complex as an ink painting.

Continuing to be guided by the philosophy of Seikatsu Kogei, Mitani-san has become renowned in Japan as a master of his craft, and his work is celebrated for its quality, beauty, and unique perspective. But still, he keeps it simple: “Basically, I make what I want to use. That’s it. To be honest, I’m not good at understanding what other people want. I’m useless at marketing. My customers are those who want the same things as me. There may not be so many, but they exist. If I can provide my work to people who are kindred to me, that’s enough.”

Well, one of those kindred spirits happened to be me. I’ve been collecting his works for over a decade, and his tableware is not only used frequently on my dining table, but they are also always on display in my living room. Such beautiful pieces should not be stacked or hidden away in cabinets. I showcase them proudly on a shelf where I can enjoy the sight of them every day.

When I sit at my desk, focused on my work for hours on end, I glance at Mitani-san’s pieces on my shelf. The uniqueness of the wood grain on their surfaces, the beauty of silhouette in each form, and the singularity of the layered colors in natural light makes me feel encouraged and at peace. It’s true that I appreciate well-made things. But there is something special about Mitani-san’s work that touches my heart.

Mitani-san once told me, “Soetsu Yanagi said that things made by human hands have a spirit that a machine could never produce, because human hands connect to the mind.” I do believe that what gives Mitani-san’s work its singular spirit is that connection to his remarkable mind. I hope that you too can feel that spirit. With this wish, I end Mitani-san’s story.

Aya Nihei is a Nalata Nalata contributing writer. She is a longtime friend of Ryuji Mitani and an avid collector of his works.

The English translation of this article has been edited by Audrey Kang

All images courtesy of Ryuji Mitani