Industrial designer Makoto Koizumi and his works are well known in the world; however, when Steve from Nalata Nalata told me that his personality and the path he has taken are not familiar, I agreed. As a consumer rather than an insider in the design industry, I associate Koizumi-san with his distinct products such as wooden chairs, enamel kettles, and wall clocks—as well as the Sumire Aoi House, which is a small, cubic architecture build of only 9 tsubo (approximately 320 sq ft.) that he redesigned. I also met him before as a writer for an interview and had a glimpse of his cheerful personality. But, wait. Who is Koizumi-san anyway? Is he a multi-disciplinary designer who works on everything from kitchen tools to housing? Why is he based in Kunitachi, the western suburb of Tokyo? Various questions came to mind. Ok, let’s ask him directly. I visited Koizumi Douguten, where he runs a shop and studio about a 20-minute walk from Kunitachi station on the JR Chuo line.

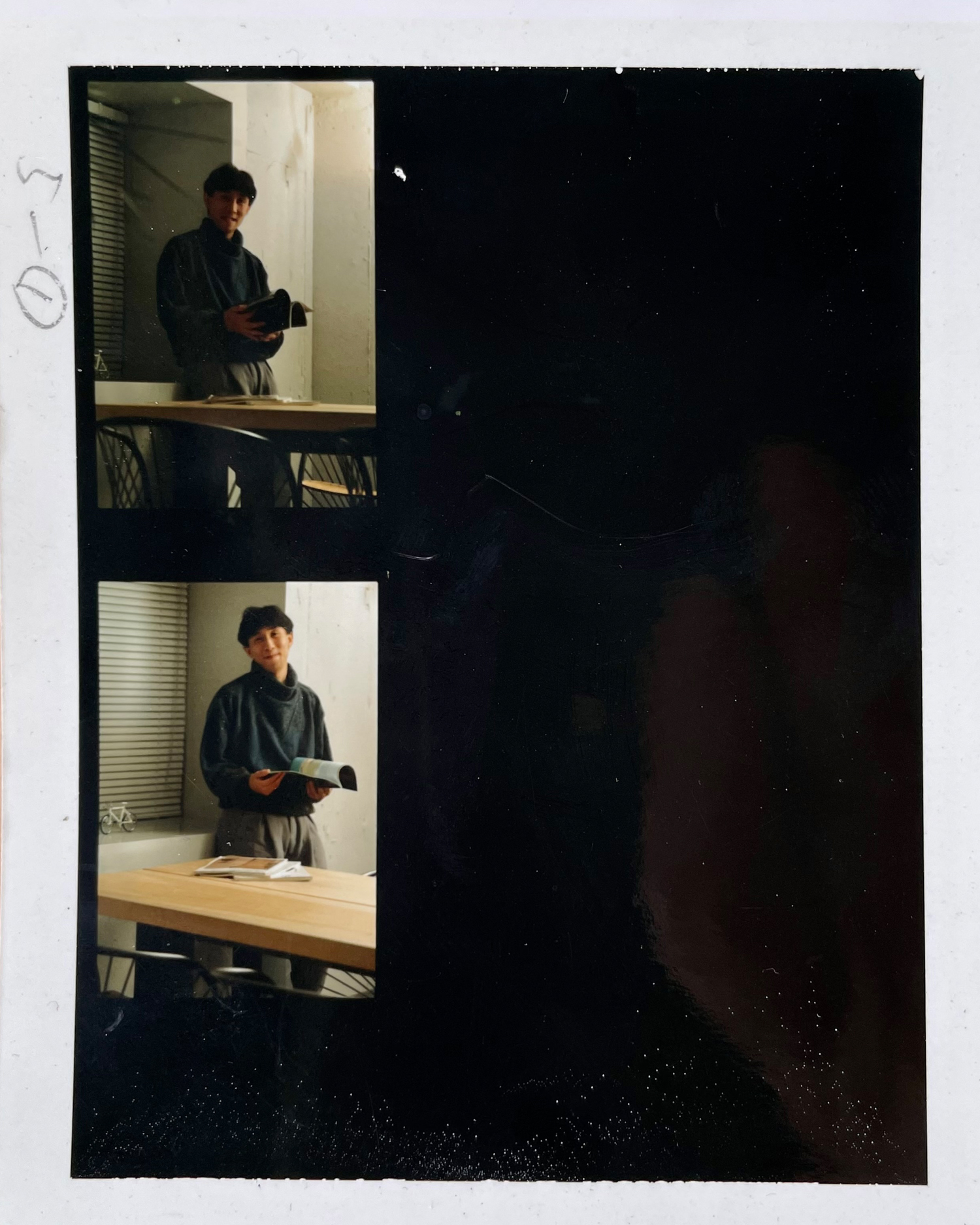

On the first floor of Koizumi Douguten, which was renovated from an old, wood-constructed shoe store, Koizumi-san greeted me with the same gentle appearance as before. First, I interviewed him about his new chair, the Tonton Rocking Chair. After that, I climbed up the ladder to the second floor and excitedly explored his secret-base-like studio. Luckily, I had a chance to admire his amazing collection of antiques. Anyway, I had a lot of fun in his studio, and we finally got started with an interview about the life story of Makoto Koizumi.

Makoto Koizumi, a furniture designer, born in 1960.

His life began with his father, a national public servant, his mother and sister in a public housing complex in Tokyo. Back in the 1960s and 1970s when Koizumi-san spent his childhood, Japan was in the middle of a period of high economic growth. “There was construction everywhere. Roads and houses were built here and there. I used to watch them with interest. When I was an elementary school student, I asked a guy at a construction site to help, and he allowed me to knead cement. He praised me, ‘Good job!’ and gave me 10 yen as a reward. Looking back on it now, I think I must have liked making things. I would say it was sort of my origin.”

Speaking of his origin, Koizumi-san says spending time at his parents’ homes was part of it too. His father’s family house was a traditional Machiya (town house) in Osaka, and his mother’s was a house in the rice paddies of Nara. “The house in Osaka was what we call old Machiya style, with a courtyard in the back adjoining from the earthen floor and bathroom outside. The house in Nara was Shoin-zukuri (traditional Japanese residential architecture) with Engawa (wooden porches). I assume I was influenced in some way by experiencing such primitive Japanese landscapes as a child.”

Doma (earthen floors), wooden Hashira (pillars) and Hari (beams), tatami rooms, Fusuma (sliding doors), Shoji (sliding doors with wooden flames and translucent paper), Tokonoma (an alcove for art display), and so on. By touching them, feeling the materials and forms, and spending time in the living space originating from the Japanese climate and lifestyle must have become unintentionally foundational. The back-and-forth between living in the city and returning to the countryside also left “something” on the boy Koizumi. He says it’s related to his move to Kunitachi in later days. For now, I set that story aside—let’s get back to his life story in his student days.

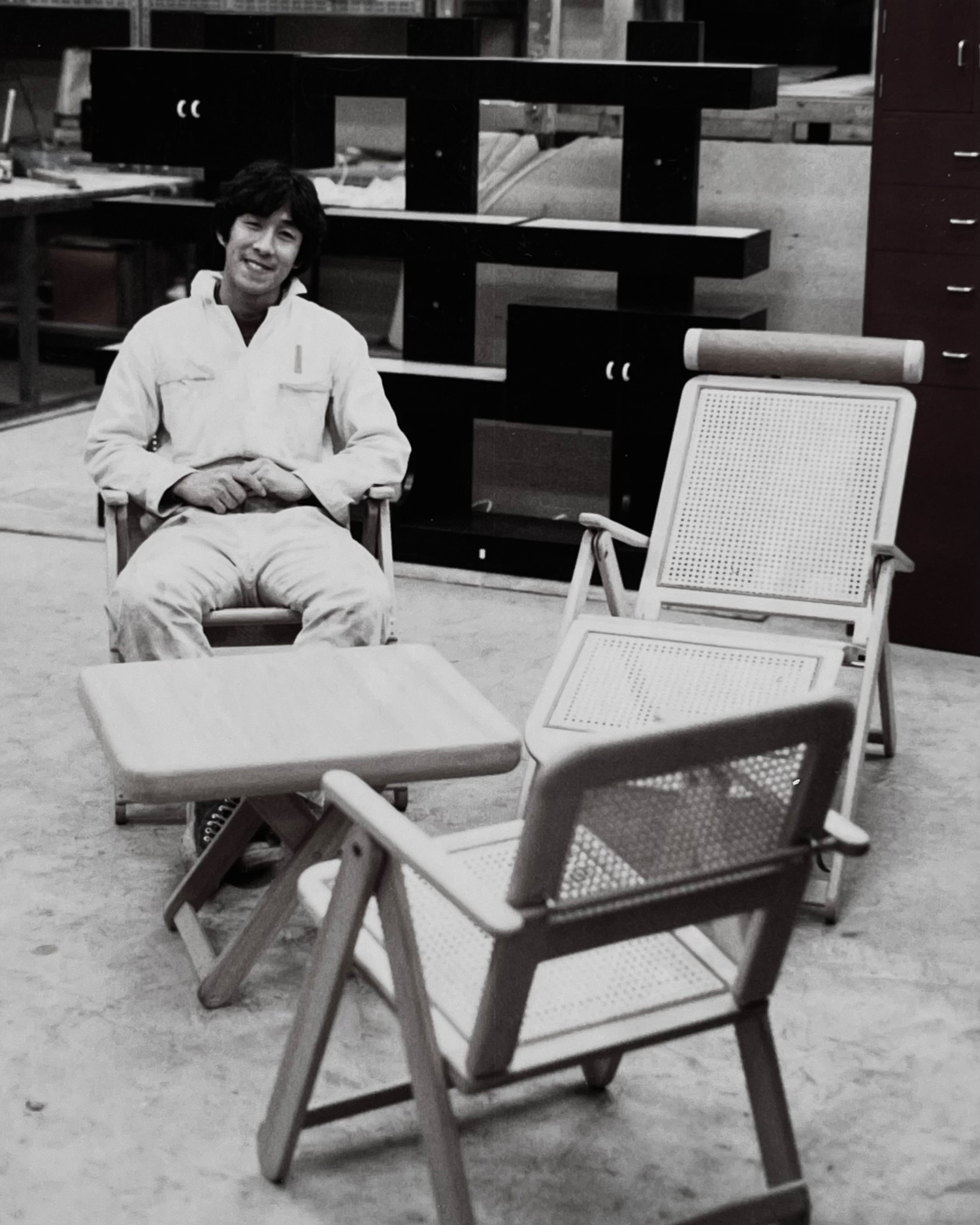

The boy Koizumi grew up into a young man who loved soccer. His father convinced him to go to university after high school, but because of his rebellious phase or his twisted character, he did not want to follow his father’s advice and went to a vocational school. He spent the first two years at an acoustics school, which he didn’t have confidence in, and then he decided to go to design school for the next two years. It was when he took a woodworking class at the design school that he became aware of his calling. His unconscious longing for craftsmanship during his childhood might have been awakened by touching wood. Finally, he found his dream of being a furniture designer, and he took the first step of his life towards it.

At design school, Koizumi-san also had a significant encounter with a key person in his life. It was Yoshifumi Nakamura, an architect who was his teacher at that time. Koizumi-san says, “He’s my mentor, or rather an intimate presence for me.” Koizumi-san and the respected Nakamura-san became acquainted in and out of the school. Their relationship has continued to the present day.

After graduation, Koizumi-san desired to work as a furniture designer, but there were no job opportunities. Although he took a position at a subcontracting company, unsatisfying jobs made his heart heavy. Koizumi-san got advice from Nakamura-san to “better go work for someone you could respect” and decided to seek out designers. With the ulterior motive that furniture design is included in interior design, he set his sights on interior designers such as Shiro Kuramata, Shigeru Uchida, and Choei Hara. Koizumi-san visited the office of Choei and Narumitsu Hara first. Fateful or not, there was an opening for an assistant, and Koizumi-san was quickly hired. He ended up working at Joint Center, the Hara brother’s office.

For Koizumi-san, Choei Hara played the role “Shu” of the “Shu-Ha-Ri[1]” in his life, “since he taught me something like a way of life,“ Koizumi-san says. “For example, when I tried to join a meeting, he stated, ‘Your attire is not appropriate. I won’t let you attend today. Do you understand what kind of people you are meeting today? Did you think about it and dress accordingly?’ He was right. I chose my outfit without any thought. I learned every single etiquette from him, such as this. He was a very strict and outspoken person; his words hit my heart. One day I even dreamt that I pushed him from the top of a building (laughs), but you know, I really respected him. Hara-san made my foundation.”

Koizumi-san also learned an attitude and mindset towards both working and living from the Hara brothers, who mainly worked on interior design for offices and commercial facilities.

“Hara-san was a person who listened to his clients’ voices and designed accordingly. He never imposed his designs on his clients based on the idea that he was the professional, nor did he only do as his clients asked. He always tried to create something special that only he and his clients could make together. That is why his design wasn’t influenced by trends. Consistent and timeless creation —I was able to learn that thanks to the master Hara.”

[1] Shu-Ha-Ri (守破離) is a concept which describes the stages of learning to mastery of Kendo or Sado (tea ceremony). Shu is the stage to learn fundamentals from the master, Ha is the stage to develop one’s mind and skill by learning from other masters, Ri is the stage to establish one’s originality.

In 1990, at the age of 30, Koizumi-san left the Joint Center after working five and a half years to found Koizumi Studio and became an independent furniture designer. At first, he made a living by helping Yoshifumi Nakamura at the rented space in his office and by doing a few commissioned works on his own. Working with Nakamura-san—who engaged in both architecture and furniture design— and helping with the detailed designs and site management of his residential projects, Koizumi-san came to a certain realization. “Furniture designers are not just supposed to make furniture as products. Furniture designers need to understand architecture. Furniture designers can’t design anything without appreciating everyday life. I recognized that clearly.”

For example, when a furniture designer designs a dining table, one should consider not only the shape and size but also the place where the table is placed and even the distance from the wall. One should be asking, “Is there enough space to go through between the table and wall,” and, “is it a space where people can eat comfortably?” Ultimately, Koizumi-san discovered that comprehensive insight about the living space and stepping into the emotional aspects of the users are a must in a furniture designer’s process. This conclusion led Koizumi-san to realize his own philosophy: a house is also a part of furniture.

“Furniture designers are people who create tools for daily life. From that point of view, I would say that a house is also one of the tools for daily life: furniture. So I came to think that I should be involved in everything from chairs, tables, tableware to houses.”

This realization led Koizumi-san to renovate his own apartment, redesign the Sumire Aoi House, re-learn architecture in his 40s, and more. Koizumi-san was in the “Ha” stage of his career (to develop one’s mind and skill by learning other masters), and it was Yoshifumi Nakamura who supported him.

Koizumi-san’s lifestyle also transformed around the same time of his independence. When his relative vacated their public housing complex, he moved to Kunitachi in the western suburb of Tokyo.

In the early 1990s, designers had their offices in prestigious locations in central Tokyo. That was the status symbol. Some must have not imagined moving to Kunitachi, an hour’s train ride from Tokyo station. Some might have even ridiculed Koizumi-san as a failure. However, Koizumi-san did not care at all what others thought.

“I felt it was rather new. In those days, interior designers commonly worked in central Tokyo, so I expected that I may be doing something new. I saw myself positively. I admit I felt far from central Tokyo though (laughs).”

Koizumi-san also sympathizes with a place that is not in the city from the back-and-forth to his parents’ homes in his childhood.

“Once I started my life in Kunitachi, I realized that I belonged here. I even felt that central Tokyo was like a different country. From Kunitachi, I was able to observe various things objectively. I also could make my stance definite.”

Koizumi-san didn’t pay attention to what was “normal” in society but followed the direction that his senses flowed. In the same way, he later opened Koizumi Douguten in Kunitachi, where he showcases and sells his works.

“It was an inconvenient location far from the train station where people wouldn’t expect a store, but I’ve visited such stores overseas and had good impressions about them as well as the towns. I hoped my store would be like that. I also felt that I could express myself freely without any stress in Kunitachi.”

After the 2000s, various stores rooted in the suburbs and countryside have increased. It’s no longer uncommon that young people move to such places. Now we know that Koizumi-san was a pioneer of such movements!

After moving to Kunitachi, Koizumi-san established his “-ism” and pursued it, reaching the stage “Ri” of Shu-Ha-Ri. One great example was his unique, collaborative way of working with manufacturers.

The event that changed Koizumi-san’s life happened at the age of 38. One day, a furniture manufacturer, for which he had designed a product, went bankrupt.

“Although the bankruptcy wasn’t caused only by my products, I was partly responsible for their bankruptcy. I couldn’t help them as a designer. That was an indescribable shock to me. I started to wonder what I was designing for.”

Back then, manufacturing something new and unique was much preferred, and selling a lot of them was demanded. Such short-lived manufacturing was rampant. Designers were recognized as means to achieve manufacturers’ purpose (good sales). Once they finish production, that’s over—no more relationships. Koizumi-san began to have doubts about such irresponsible and unsustainable manufacturing. Just then, he came across the Miyazaki Chair Factory based in Tokushima.

It was 23 years ago, in the year 2000.

In those days, Miyazaki Chair Factory was a subcontractor for furniture manufacturers and “they were just forced to make things,” Koizumi-san says. Katsuhiro Miyazaki, the CEO of the company, tried to break out of the situation and launch their own brand. He then approached Koizumi-san.

“Ok, well, here is my design for you. Let’s make a nice chair!” Of course, Koizumi-san didn’t suggest so or handed over his designs. Koizumi-san believed that he should face a manufacturer first and decided to visit their factory every two months. “You know, it was like a marriage.” As Koizumi-san refers to it, he and Miyazaki-san started manufacturing by spending time getting acquainted and talking a lot in person in order to build a relationship.

Their manufacturing process, called a workshop, was unique. Koizumi-san drew a rough sketch, then Miyazaki Chair Factory created a full-scale prototype based on the sketch. Surrounding the prototype, Koizumi-san, Miyazaki-san, and the staff at the factory brainstormed and verified each detail and usability. After that, Koizumi-san adjusted his sketch, and the Miyazaki Chair Factory created an improved prototype. Surrounding the prototype again, verifying again, then creating again another prototype. Repeat. The process was tremendously time and labor-consuming, but it resulted in creating distinctive products full of ideas, techniques, and love. Also, it took time to be recognized and sold, since the products were not ordinary. They believed that making and selling patiently, persistently, and slowly would make the products be cherished sustainably. The concept was sustainable manufacturing. Koizumi-san calls it “manufacturing with determination.”

“Think about marriage. The products we create together are like our children. If you love your children, you want to take good care of them and raise them responsibly forever, right? It’s the same as our products. To do so, we need to make up our minds and be committed.”

Such manufacturing also brought unexpected results. “Miyazaki-san changed. The direction of the company changed. The mindset of staff changed. Young, new employees came to join and the company got energetic. I could see everyone’s complexion changed.”

From that successful experience, Koizumi-san began to pursue slow yet diligent manufacturing with other manufacturers. He has gotten positive results like the case of Miyazaki Chair Factory, one after another.

“It’s not about what we make, but who we make it with.”

Koizumi-san says that is the root of his manufacturing.

“Creating something with others is my pleasure. It’s also a pleasure for the staff and for everyone involved. When my partner and my staff are happy, it makes me very happy as well. After all, it’s all about the people.”

Contrary to his calm design, what a passionate and idealistic man Koizumi-san is! I stated this to him so honestly. Koizumi-san laughed and said, “Yes, yes, you are right. I’m often thought of as an annoying, avid designer. People often think of me as a person who is hard to deal with (laughs).”

“But,” Koizumi-san continued, “it’s obvious that as the population will decline, the number of makers will decline too. We will have to slow down or change the scale in order to survive. I think we should take more time and put more of our feelings into manufacturing. The reason why people don’t do that is that it is bothersome and expensive, but I’m sure we will discover something, or be able to perceive something after that.”

In a world where rationality, efficiency, and productivity are prioritized, Koizumi-san is moving forward impulsively in the very opposite direction. And yet, there’s something fresh about the trail he leaves that intrigues us, like when he moved to Kunitachi in the past.

“I believe that it’s important to do unnecessary things,” Koizumi-san also says.

During the pursuit of efficiency, we overlooked, omitted, or neglected a lot of things. “Working on such things sincerely will have to become more important for us from now on.”

For some people, this may sound like a fantasy by an idealist, but I took his words as a positive prediction. I felt it as the indubitable light Koizumi-san shines on our near future. Well, then, let’s move toward the light. I would be happy if you could think so and if you could be motivated, encouraged, or excited somehow. I believe that is what makes the Makoto Koizumi life story worthwhile.

Archive images courtesy of Koizumi Studio.